Shugri Nour, Navisha Weerasinghe

As Registered Nurses working in busy hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area, we see the approach of Waste Reduction Week as an opportunity to reflect on what the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated proliferation of personal protective equipment (PPE) has shown us about health sector waste.

Over the course of the pandemic, PPE has become a part of not just public consciousness, but everyday life. Along with our keys, wallets, and phones, grabbing a mask before we head out the door is quickly becoming second-nature. In addition to its embeddedness in our daily routines, PPE features heavily in almost all social and congregate settings; it is, in a word, ubiquitous.

Even for those of us for whom PPE has long been part of our everyday professional lives, the pandemic ushered in unprecedented PPE use. Hospitals in Canada mandated that all patients, visitors and healthcare workers wear masks upon entry into the hospital and remain masked while indoors, contributing to an immediate and significant increase in mask use.

Heightened precautions to mitigate the spread of the COVID-19 virus warranted increased use of isolation status, which resulted in increased use of PPE. Patients with a diagnosis of, or under investigation for, COVID-19 are placed on droplet and contact precautions; this necessitates that any healthcare professionals entering the room wear the required PPE such as gloves, masks, gowns and face shields, even if they are not providing care. Early on, when the virus was new and not well understood, many individuals who presented with COVID-19 related symptoms required isolation in hospital; a number of whom would go on to be cleared by negative COVID-19 swab results within 24 hours. COVID-19 consists of an array of typical and atypical symptoms that often mirror other conditions. For example, symptoms such as shortness of breath and/or headaches, which did not require isolation precautions prior to the pandemic now call for isolation.

In addition, depending on the patient’s presentation and oxygen needs, those in critical status may require high flow oxygen and/or intubation with ventilation. These procedures place healthcare workers at additional risk, demanding the use of added PPE such as N95 masks and specialized gowns. Moreover, due to isolation protocols, any excess supplies or equipment brought into a patient’s room must be disposed of once the patient is cleared or discharged, contributing to waste.

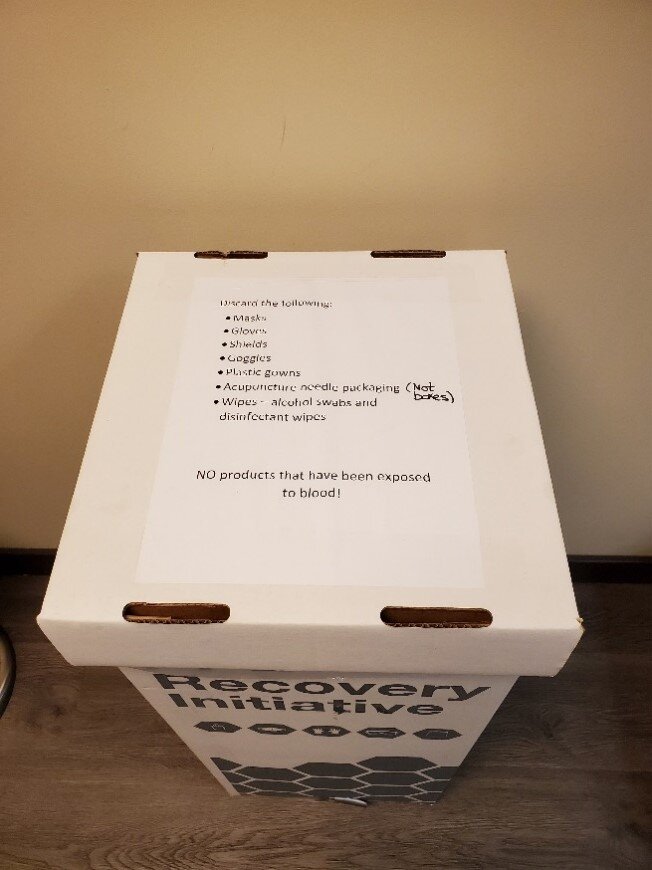

The vast majority of PPE and other supplies used in this context are single-use disposable items and were either discarded in the garbage or biohazard bags. Early on in the pandemic, hospitals and care settings were threatened with a potential PPE shortage, due to the sudden uprise in use. In response, many hospitals transitioned into recycling N95 masks as a contingency plan to sterilize masks for reuse come a dire shortage in the pandemic. Another change was the shift from disposable gowns to reusable gowns requiring washing. While the recycling program was short-lived once N95 supply proved consistent, the reusable gowns sustained, and as a result, this reduced waste production and fostered environmental benefits via waste diversion.

When we reflect on how many disposable gloves, masks, gowns and face shields we have been using individually in our respective work settings since the pandemic began, we cannot help but think about how this adds up globally. Although COVID-19 continues to be a threat and the use of PPE is necessary, the massive amounts of PPE waste generated over the past 18 months has heightened our awareness that the type of PPE we use, and the ways in which we dispose of it, require careful consideration.

Waste Reduction Week, which is part of a year-round program that promotes action and celebrates efforts in building environmentally conscious practices while encouraging sustainable, innovative ideas and changes, is a good time for the healthcare sector to take stock of its supply chain, from procurement to disposal. This year, Waste Reduction Week is taking place between October 18-24, 2021; each day will highlight a different theme, including the Circular Economy, Textiles, E-waste, Plastics, Food Waste, the Sharing Economy, and Swap and Repair.

While this national event is not directly aimed at the health sector, these are all areas of relevance to health system sustainability. Let us use the lessons we have learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and the growing specter of PPE waste as inspiration to demand, create, and implement comprehensive changes that promote sustainability of all hospital resources, which span from supply chains to waste streams. These approaches can then mitigate the health system’s significant environmental impact.

PPE waste sheds light on the various types of waste that hospitals produce, broadening the scope for action. We must hold healthcare systems accountable for their part in generating waste and waste-related carbon emissions and work collaboratively as a global community to develop innovative solutions to decrease PPE waste and all healthcare-related waste. This is something that should be a priority for all healthcare professionals.

About the authors

Shugri Nour is a Registered Nurse working in Hemodialysis for 5 years. She completed her Master of Nursing (MN) at U of T. Shugri is currently a Research Assistant at the Centre for Sustainable Health Systems where she is involved in developing content on sustainable food in healthcare.

Navisha Weerasinghe is a Registered Nurse working in the Emergency Department and Med/Surg units in GTA hospitals. Navisha recently completed her Master of Nursing (MN) - Clinical program at the University of Toronto. Navisha is currently a Research Assistant with the Centre for Sustainable Health Systems. Her interests include greening healthcare systems and finding innovative solutions to reduce ward waste in healthcare settings.

All CSHS guest posts are published under the CreativeCommons Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike license. Guest Contributors are free to publish their guest posts elsewhere.

If you’ve got an idea for a blog post you’d like to author, please contact us.